Is addition of N-Acetyl Cysteine to Clomiphene Citrate Beneficial for Ovulation Induction in Anovulatory Infertility?-Juniper Publishers

Global Journal of Reproductive

Medicine Juniper

Publishers

Authored by: Neha Garg*

Introduction

Infertility has been a growing global public health issue. It affects one in every six couples, which is 15% couples in reproductive age group. Female factor infertility accounts for 40% [1]. Around 15% of all infertile couples and in 40% of infertile women anovulation is the cause [2]. Clomiphene citrate has been traditionally used as the first line drug in anovulatory infertility. But as a singular drug it may not be effective in all cases. Thus, the need for an adjuvant which is a drug or a substance that enhances the activity of another or a substance added to a medicinal preparation to assist the action of the principal ingredient. Aspirin, L-arginine, oestrogens, glucocorticoids, spironolactone, cyproterone acetate, dehydroepiandrosterone, metformin, etc. are some of the adjuvants being used. Considering the high prevalence of insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemias as the most common etiological factors for resistance to clomiphene as seen in most cases of anovulatory infertility because PCOS contributes about 80% of cases with anovulation. Attention is being given to adjuvants with insulin-sensitizing properties [3]. Recently, N-acetyl cysteine (NAC) was suggested as one of such adjuvants [4]. The encouraging preliminary reports and the myriad of actions of NAC prompted us to investigate its effects on promoting the action of clomiphene citrate on ovulation.

Objective

To investigate the effects of N-acetyl cysteine in promoting the augmenting effects of clomiphene citrate on ovulation in all cases of anovulatory infertility by comparing the efficacy of combination of clomiphene citrate with N-acetyl cysteine vs clomiphene citrate alone.

Materials and Methods

• Health care setup – Tertiary care hospital

• Setting- JJM Medical College, Davangere, Karnataka.

• Duration of the study - 2014 to 2018 (4 years)

• Type of the study - Prospective cohort study

• Sample size - 117

• Level of evidence - Level IV

• Selection of cases- 117 cases of anovulatory infertility were taken who satisfied the inclusion and exclusion criteria of the study.

Inclusion criteria

I. All cases of primary and secondary infertility with anovulation

II. Patients with bilateral fallopian tubes patent observed at laparoscopic chromopertubation, or hysterosalphingography or sonosalphingography.

III. Their spouse should have male factor fertility confirmed by adequate seminal parameters according to latest WHO guidelines.

Exclusion criteria

i. Patients with regular menstrual cycles

ii. Patients with tubal blockage identified at HSG, laparoscopic chromopertubation, or sonosalphingography

iii. Clinical evidence of hyperprolactinemia, hypercortisolism, or thyroid dysfunction

iv. Patients with unexplained infertility

v. Male infertility

vi. Patients refused participation as per our protocol

After getting IEC clearance from the institute and written informed consent from the patients enrolled in our study, they were subjected for thorough examination for confirmation of anovulation [5,6], as the cause for infertility. These patients were either given oral contraceptive pill (OCPs) if they came within 5 days of their menses or progesterone pills if they had a history of previous amenorrhea after ruling out pregnancy. In next menstrual cycle, within 3 days of their menses, ovulation induction using two different regimens were started for them.

Randomization was done by coin-tossing method into two groups

i. Group CC: 61 cases were given tablet clomiphene citrate alone 100 mg/day orally from day 3 to day 7 of the menstrual cycle.

ii. Group CC-NAC: 56 cases were given tablet clomiphene citrate 100 mg/day along with tablet N-acetyl cysteine 1200 mg/day orally from day 3 to day 7 of the menstrual cycle.

• Follow up – All the patients were asked to report back on 9th to 16th day of menstrual cycle. Transvaginal ultrasound for follicular development and endometrial thickness was done on 14th-16th day of the cycle. Advice for timed intercourse daily around the time of ovulation was given.

• But if a dominant follicle was not found in both the ovaries and multiple small follicles were found less than 10mm, we considered that she would not ovulate in that cycle and was asked to review in the next cycle.

• Next menstrual cycle – Defaulters with inadequate follicular development in previous cycle were once again treated with same regimen. In the absence of menstruation, diagnosis of pregnancy was confirmed by either urine pregnancy test/ bimanual examination/ TVS. But if not found to be pregnant, progesterone induced withdrawal bleeding was given and same regimen was given. Treatment was given for a maximum of 3 cycles.

• Main outcomes measured were number of follicles, endometrial thickness, ovulation rate, pregnancy rate and miscarriage rates.

• Statistical Analysis were reported as mean (SD) for continuous variables, frequencies (percentage) for categorical variables. Data were statistically evaluated with IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 20.0, IBM Corp, Chicago, IL.

Results

The patients who underwent treatment as per our study protocol were analysed statistically with student ‘t’ test and chi square test and the results were tabulated.

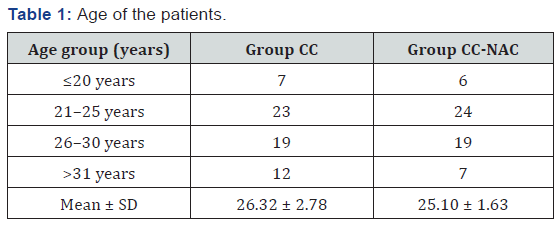

The majority of patients in Group CC and Group CC-NAC were in the age group of 21-25 years. Minimum age was 18 years and maximum age was 36 years. This shows that anovulation was found to be more common between the age of 21-25 years which is the period of maximum fecundity (Table 1).

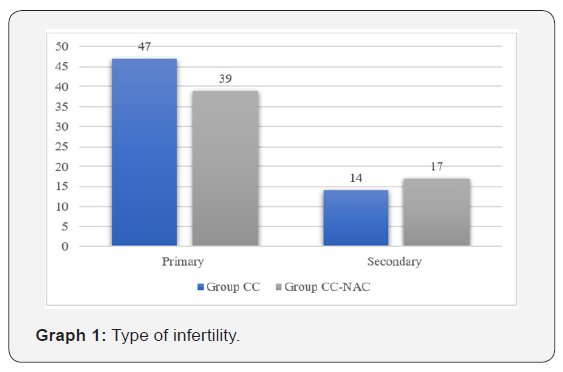

Type of infertility

In both the groups, primary infertility was found to be more common than secondary infertility (Graph 1).

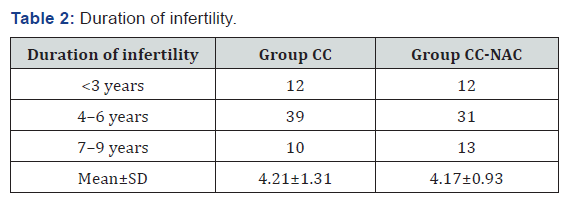

Duration of infertility

The mean duration of infertility in Group CC was 4.21 ± 1.31 and in Group NAC was 4.17 ± 0.93 (Table 2).

Tubal patency testing

Out of 117 cases, Laparoscopy were done in 38 cases (32.47%) and anovulatory ovaries were seen in 17 cases (44.73%) in group CC and 21 cases (55.26%) in group CC-NAC. In another 79 cases(67.52%), sonosalphingography was done in 48 cases (60.75%) [Group CC- 25 (52.08%), Group CC-NAC- 23 (47.91%)] and HSG in 31 cases (39.24%) [Group CC-15 (48.38%), Group CCNAC- 16 (51.61%)].

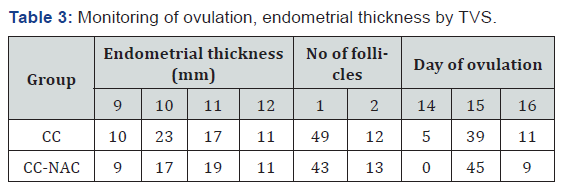

Monitoring of ovulation, endometrial thickness by TVS

(Table 3)

Endometrial thickness

The mean endometrial thickness in group CC was 10.17 ± 1.01 and in group CC-NAC was 12.19 ± 1.36 (Table 4).

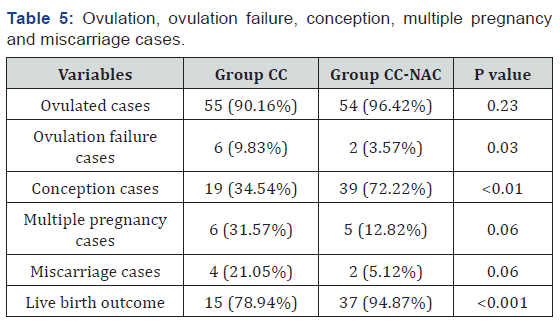

Ovulation, ovulation failure, conception, multiple pregnancy and miscarriage cases

In group CC (n=61), a total of 55 cases ovulated, 19 cases conceived, 6 cases had miscarriage and 4 cases has multiple pregnancies. In group CC-NAC (n=56), a total of 54 cases ovulated, 39 cases conceived, 5 cases had miscarriage and 2 cases has multiple pregnancies. There is a significant statistical difference (p<0.001) in the outcome rate in terms of live birth which was found higher 37 cases (94.87%) in group CC-NAC 37 while comparing with 15 cases (78.94%) in group CC (Table 5) (Graph 2).

Conceived cycles

The Spearman’s Rank correlation analysis were done which show highly positive correlation (ρ=0.8) between clomiphene citrate – N-acetyl cysteine and number of pregnancies and weak correlation (ρ<0.1) between clomiphene citrate and number of pregnancies in our study. The outcome in terms of number of pregnancies between Group CC and Group CC-NAC were statistically significant (p<0.01) (Graph 3).

Discussion

Anovulatory infertility is classified according to WHO into 3 categories out of which category 1 and 2 is amenable to treatment with ovulation induction. Clomiphene citrate [7], traditionally has been the gold standard drug for ovulation induction. It is a non-steroidal triphenylethylene derivative with both estrogen agonist and antagonist properties. Due to its structural similarity to estrogen, clomiphene competes for and binds nuclear estrogen receptors throughout the reproductive system. It acts centrally by reducing estrogen negative feedback and consequent increased pituitary gonadotropin release which in turn drives ovarian follicular development and ovulation. However, as a singular drug it is not equally effective in all situations. It has variable success rates in anovulatory women, lower especially in those with PCOS with insulin resistance. Majority (80%) of cases of anovulatory infertility are due to PCOS [8], thus making insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia prevalence very high among cases [9].

Others causes being stress related, Sheehan’s syndrome, anorexia nervosa, Kallmann’s syndrome, etc. [7]; but in our study all cases of anovulatory infertility has been taken into account and further categorization into the specific causes for the same has not been done.

N-acetyl cysteine, acetylated precursor of L-cysteine and reduced glutathione [10], is a commonly used mucolytic drug. Due to its multiplicity of action, it is the most desirable adjuvant to augment ovulation induction. It softens the tenacious cervical mucous secretions and overcomes the peripheral antiestrogenic hostile effect of clomiphene [11] and thus has a higher pregnancy rates if combination regimen (clomiphene + NAC) is used [4]. The antiapoptotic effects of NAC [12] are responsible for significantly higher number of follicles as it is well known that apoptosis is the main mechanism involved in follicular cohort atresia. NAC was found to inhibit apoptosis in cultured ovarian primordial germ cells [4]. NAC causes insulin secretion in pancreatic cells and regulates insulin receptors in human erythrocytes. Thus, has a proven insulin sensitizing action [13,4]. Furthermore, it is a powerful antioxidant and a potential therapeutic agent in the treatment of diseases characterized by generation of free oxygen radicals [13]. The biological activity of NAC is attributed to its sulfhydryl group which enhances glutathione -S-transferase activity aiding in the protection of all cells and membranes [14].

Various studies done in the past decades have shown promising results with additional usage of NAC along with the standard clomiphene citrate for ovulation induction. In 2005, an RCT on 150 women with PCOS (4) showed that endometrial thickness was more in the group CC-NAC (5.9± 0.7mm) as compared to CCplacebo (4.9 ± 1.9mm); (p>0.05) but was statistically insignificant. Ovulation and pregnancy rate were higher with NAC (49.3%; 21.3%) than in the control group (1.3%; 0%), p<0.0001which was statistically significant. 5 cases of multiple pregnancies, 2 cases of miscarriages (12.5%) (1 singleton and 1 multiple pregnancy) and no cases of OHSS were reported in NAC group. In 2012, Salehpour et al. [15] concluded that the number of follicles >18mm, mean endometrial thickness, ovulation and pregnancy rate were significantly higher among CC-NAC group (p=0.001, p=0.02 & 0.04 respectively). No adverse side-effects and no cases of ovarian hyperstimulation were observed in group receiving NAC. A metaanalysis conducted by Thakker et al. [16], where 8 RCT with 910 women with PCOS effects of NAC were compared with placebo/ metformin. NAC significantly improved rates of live births and spontaneous ovulation compared to placebo. However, it was not associated with greater benefits to metformin for improving pregnancy rate, spontaneous ovulation and menstrual regularity. Maged AM et al. [17], in an RCT in 2015 showed that NAC as an adjuvant to clomiphene improves ovulation and pregnancy rates in PCOS patients with beneficial impacts on endometrial thickness as compared to the both groups (CC alone and CC with metformin) [17].

On the other hand, in the recent RCT on 97 PCOS women in 2017, results showed no significant differences in the study group (NAC +CC+ Letrozole) vs (CC + Letrozole) regarding mean endometrial thickness (p=0.14), mean number of mature follicles (p=0.20), and pregnancy rate (p=0.09) [18]. This was in contrast to the findings of our study which highlights the effectiveness of NAC. However, all these previous studies have been exclusively done on women with PCOS which is a subset of all the various cases of anovulatory infertility. Thus, data proving effectiveness of NAC in all cases of anovulation is scarce and our study throws light in this direction.

Endometrial thickness, which is the maximum distance between the echogenic interfaces of the myometrium and the endometrium measured in a pane through central longitudinal axis; was found to be higher in CC-NAC group (12.19 ± 1.36mm) as compared to CC group (10.17 ± 1.01mm). Ovulation and conception rate were also higher in CC-NAC group (96.42%;72.22%) than with CC group (90.16%; 34.54%). Clinical pregnancy rate was 94.87% in the combination group which was statistically higher than in CC group (78.94%); p< <0.001. More monofollicular stimulation and thus lesser cases of multiple pregnancy (12.82%) was in CC-NAC group than in CC group (31.57%). Miscarriage rates were higher in CC group (21.05%) as compared to CC-NAC group (5.12%). However, our study was limited to 3 treatment cycles. No cases of ovarian hyperstimulation were reported. N-acetyl cysteine was well tolerated by all patients and no adverse effects were observed.

Conclusion

N-acetyl cysteine may be a novel adjuvant to clomiphene citrate in inducing or augmenting ovulation. It is simple, well tolerated and inexpensive agent. The route of administration is simple (oral) and monitoring of patients is by non-invasive method (TVS). It could be used as an alternative to other insulinsensitizing agents like metformin.

Comments

Post a Comment