Can Multiple Illnesses Plus HIV Trigger Integrated Care?-Juniper publishers

Global Journal of Reproductive

Medicine Juniper

Publishers

Authored by: Graham F Watts*Introduction

Duval County, (a.k.a., Duval), is a region of national significance. It is in the southern region of the United States. The South has 16 states and one territory:

a) Alabama,

b) Arkansas,

c) Delaware,

d) District of Columbia,

e) Florida,

f) Georgia,

g) Kentucky,

h) Louisiana,

i) Maryland,

j) Mississippi,

k) North Carolina,

l) Oklahoma,

m) South Carolina,

n) Tennessee,

o) Texas,

p) Virginia, and

q) West Virginia.

Duval is also home of Jacksonville, an 840 square miles city by land mass—the largest city in the contiguous United States [1]. The Global Positioning System coordinates that define the latitude and longitude of Jacksonville, FL, USA are 30° 19’ 55.8624’’ North and 81° 39’ 20.3292’’ West. It is situated near St. Johns River and is an important tourist attraction for all kinds of travelers [2].”

In addition to tourism, Jacksonville is also known for its military influence. “The waters off Jacksonville… [accommodated] German-U-boat activity during World War II…, and the city was the nation’s busiest military port during the Persian Gulf War, (1990-91) [3].” In 2017, the population of Jacksonville, Florida was 92,064 with a median age of 35.8 years and almost 2/3 , (64%), of residents were in the 18 to 64 years age-group. Four of five, (82%), inhabitants identified as either White, (51%), or Black, (31%). One-tenth of the population is Hispanic. Median household income was $51,497.00 and 15.1% of the populace lived below the poverty line,[4] which “…for a household of four is an annual income of $25,750.00 [5].” For marketing purposes, Florida’s First Coast, or First Coast describes five counties, (Baker, Clay, Duval, Nassau, and St. Johns—BCDNS), that surrounds Jacksonville [6].

Duval County is gaining notoriety. The county’s 2017 health status summary profile illuminates the area’s disease burden. Almost one in five adults, (18.5%), are current smokers compared to 15.5% in Florida. Nearly 1/3 (30.7%), of adults are obese compared to 27.4% in Florida. About 1/5 , (18.9%), of adults could not see a doctor at least once in the past year due to cost compared to 16.6% in Florida. Approaching 1/5 , (16.7%), of adults have been told they had a depressive disorder compared to 14.2% in Florida. Two-thirds, (66.5%), of pregnant women initiated early, (first trimester), prenatal care compared to 78.3% in Florida. Chlamydia cases per 100,000 was 720.8 compared to 470.3 in Florida. Gonorrhea cases per 100,000 was 297.8 compared to 138.5 in Florida [7]. Age-adjusted hospitalization rate per 100,000 for stroke was 317.2 compared to 234.7 in Florida. Ageadjusted hospitalization rate per 100,000 for congestive heart failure was 1,721.8 compared to 1,158.0 in Florida. Age-adjusted hospitalization rate per 100,000 for coronary heart disease was 323.5 compared to 293.7 in Florida [8]. Of 67 Florida counties, in 2019, Duval County ranked 44th on five health outcomes indicators: premature death, poor or fair health, poor physical health days, poor mental health days, and low birthweight [9].

Duval County has a reputation for the Human Immunodeficiency Virus, (HIV). Parallels exist between Duval County, Florida and the southern United States. In 2017, new HIV diagnoses was highest in the South, (52%, 19,968), relative to the West, (19%, 7,270), the Northeast, (16%, 6,011), and the Midwest, (13%, 5,032). Even with standardization of HIV infection rates, the South (16.1/100,000), tops the list, followed by the Northeast, (10.6/100,000), the West, (9.4/100,000), and the Midwest, (7.4/100,000) [10]. In same year, Florida ranked third, (22.9/100,000), on the list of top ten states for new HIV infections among adults and adolescents [11], and Duval County, Florida is one of 48 counties in the nation with high rates of HIV incidence [12]. How is Duval County like the southern United States? Of the five counties, (BCDNS), surrounding Jacksonville, new cases of HIV infections, in 2017, were three to four times higher in Duval County, (32.6 per 100,000), compared to surrounding Counties: Baker, (7.4/100,000), Clay, (9.5/100,000), Nassau, (7.5/100,000), and St. Johns, (10.0/100,000) [13].

Duval County HIV health services professionals give extraordinary attention to the epidemiology of HIV. This attention is matched by the allocation of resources to address the virulence of this pandemic, which, if left untreated, wipes out the host immune system, resulting in poor health and certain death. The advent of and advances in antiretroviral therapy, (ART), treatments support immune system reconstitution and viral suppression, which prolongs life. But research by Deeks & Lewin et al. [14], also showed that the therapeutic benefits of ART comes at a price—occurrences of non-communicable chronic diseases such as cancer, heart disease, kidney disease, liver disease and neurocognitive disease to name a few. A U.S. Veterans Administration study found a 1.5- fold increased risk of myocardial infarction among HIV-infected adults [15]. In contrast, the 36-months, Swiss HIV Cohort Study pointed to excess occurrences of diabetes, osteoporosis, stoke, and myocardial infarction among study participants 50 years and older compared to the younger, (less than 50 years), age-group [16]. HIV medication, which promotes living longer with HIV also requires attention to multimorbidity. “Older persons living with HIV, (PLWH), often defined as age 50 years and older, are a rapidly growing population, with high rates of chronic pain, substance use, and decreased physical functioning.”[17].

Health services professionals in Duval County have also begun to focus on multimorbidity in HIV health services. They recognize that the well documented occurrence of morbidities in aging persons living with HIV, (PLWHs), is a call to action. Because Multiple Chronic Conditions, (MCC), tax human resources in areas such as medical visits, medication adherence, and chronic diseases self-management responsibilities, relative to a single medical condition, there is growing awareness that MCC can decrease quality of life by increasing stressors and disabilities [18].

An inventory of the HIV health system “…free, electronic health and social services information system for Ryan White HIV/AIDS program grant recipients and [subrecipients] [19], highlighted the lack of an index of multiple chronic diseases. A disease index, if populated, can automatically generate a score that prompts clinical action by activating specific clinical pathways. The purpose of this study was to justify development of a cumulative index of common non-communicable diseases among PLWHs that has rapid assessment potential for differentiating clients with complex care needs. The existence of such an electronic instrument can prompt fast and timely alignment of clinical resources for more effective service utilization. The added value of this dimension to current clinical processes can ensure provision of less fragmented HIV care and services.

Materials and Methods

Exploratory study 1

Three HIV Community Based Organizations, (CBOs), completed 121 chart reviews during the first quarter of 2017. Chart selection criteria used convenience sampling and no socio-demographics data were recorded. This study was implemented as an unfunded project using staff already burdened by large, (70+), caseloads, who perceived it largely as data for health policy rather than direct patient care. Project planners yielded to ease of imple mentation as a compromise with health services staff who used personal time to assist with chart extractions. Three Medical Case Managers, (MCMs), used a standardized worksheet to perform the extractions. The worksheet, formatted as an m by n table, had 13 rows and eight columns. The rows represented morbidities of a sociological, psychological, physiological, and chemical brain imbalance origin. Morbidities of a sociological origin focused on homelessness and interpersonal violence. Morbidities of a psychological origin focused on depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation. Morbidities of a physiological origin focused on diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, cirrhosis, kidney dysfunction, cancer, and obesity. The single chemical brain imbalance morbidity examined was substance use disorders. The columns bifurcated into two divisions, one for the duration and the other for severity. The duration column had three levels: less than one year, (coded 1), one to five years, (coded 2), and more than five years, (coded 3). In contrast, the severity column had five levels: normal, (coded 1) mild/minor, (coded 2), moderate, (coded 3), severe/major, (coded 4), and end-stage/extreme, (coded 5). The instructions to MCMs familiar with the convenience sample of clients asked for placing two check marks, (), in each row, if indicated, in the duration and severity columns for every morbidity documented in the charts. Data analysis relied on frequencies, percentages, and the sum of products-which first multiplies then adds the multiplicative values to create a sum. This approach is superior to a simple additive sum [20] of multiple chronic diseases which quantitatively ignores the burden of duration and severity of illness on health and social functioning.

Exploratory study 2

At one of the three HIV CBOs, the University of North Florida, Center for Nutrition and Food Security developed assessments tools. These assessments examined the nutritional status of a convenience sample of clients with HIV and their nutritionrelated complications. Currently, all clients in the local Ryan White network lack access to a validated nutrition-screening tool to identify whether personal health is impaired by the lack of high quality, disease-therapeutic foods in enough quantities. Therefore, the University of North Florida’s nutrition professionals developed a disease-specific nutrition-screening tool based on research and practice experience. Data analysis relied on frequencies and percentages.

Nutrition HIV screening tool & methodology

Appropriate nutrition screening tools is an essential component of comprehensive health care for PLWHs. Hence, the development process included a scoping review of the nutrition literature, identification of nutritional parameters relevant to PLWHs, and discussions about questionnaire length, reading level, format, and frequency and timing of administration. These considerations, among others, have implications for the collection of accurate and valid data. The screening tool has six items that includes insufficient money to purchase food, worry about having an adequate supply of food, body mass index, recent, (past six-months), HIV diagnosis, metabolic and cardiovascular diseases, (diabetes, heart disease or hypertension), contemporary, (past six-months) weight lost, and gastrointestinal issues such as difficulty swallowing, nausea with vomiting, poor appetite, and chronic diarrhea. The additive sum of the points assigned to each item ranged from 0 to 17, which allowed the researcher to triage respondents into three nutritional status categories: normal, (0 to 3), at nutritional risk, (4 to 6), or high nutrition risk, (7 to 17). The rationale for selection of cut-points was facilitation of extensive nutrition screening.

Electronic health & social record updates

Duval County HIV health services Information Technology data manager hard-coded the inventories in the network’s electronic health and social record. Services staff received data collection training and practiced on peers using simulated data. Once trainings were completed, staff evaluated client’s comprehension of inventory questions and statements. Client feedback were incorporated into revisions and trained medical case managers subsequently administered the instrument by screening active clients during a 90-days trial period. The screening protocol also tested a linkage process to connect clients identified at nutritional risk or high nutrition risk to a registered dietitian for a complete nutrition assessment and development of a plan of care. Although exploratory study 2 was unfunded, it garnered strong support from Case Managers because it resulted in direct benefits to clients in referrals and linkages to a Dietitian. Access to timely nutrition services is essential to address underlying unmet needs for food that supports tissue repair and maintenance, immune system support, and metabolism of antiretrovirals [21].

Results

Exploratory study 1

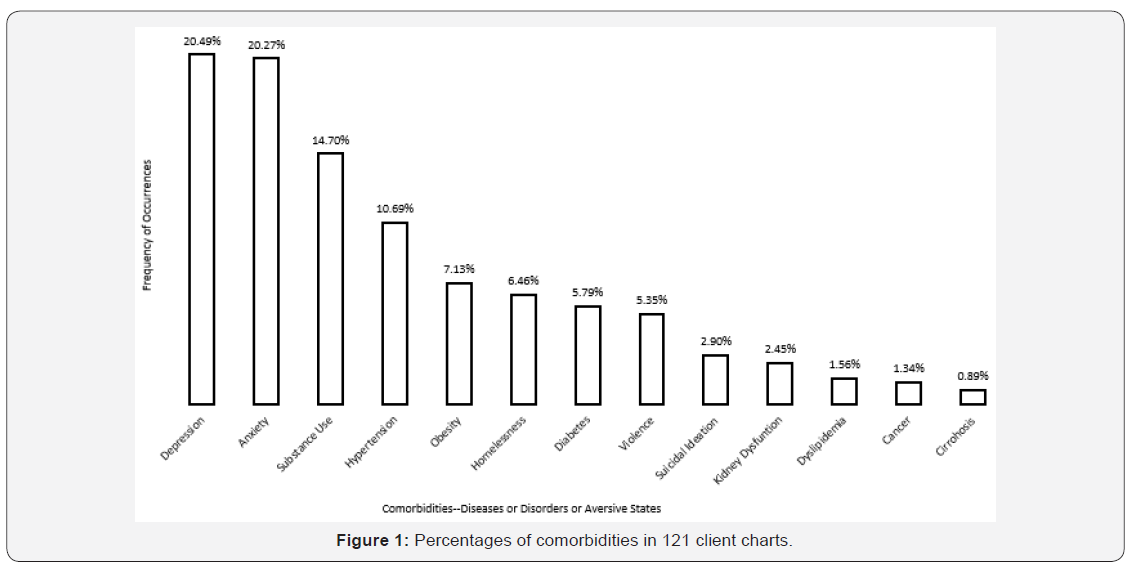

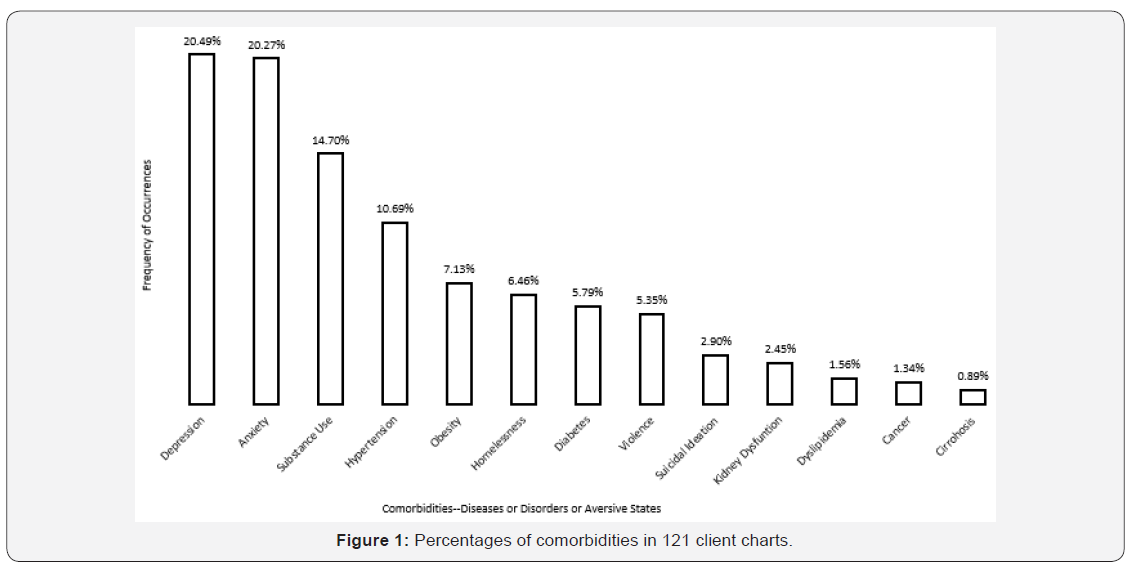

Figure 1 presents the frequency of occurrences of 13 conditions compiled from 121 PLWHAs chart reviews. Comorbidities involving psychological and chemical brain imbalances were most prevalent. This included depression, (20.49%), anxiety, (20.27%), and substance use disorder, (14.70%). The second most prevalent set of comorbidities were metabolic states, identified by hypertension, (10.69%), obesity, (7.13%), and diabetes, (5.79%). On the sociological side, homelessness (6.46%), and interpersonal violence, (5.35%), were most prevalent. None of the remaining conditions exceeded 3% in the sample.

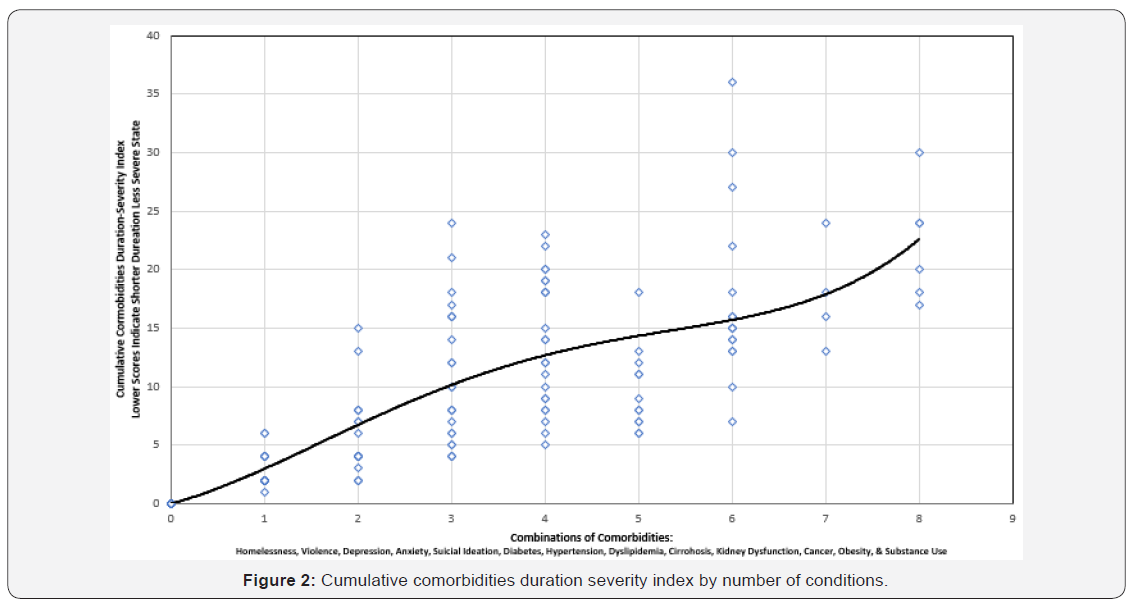

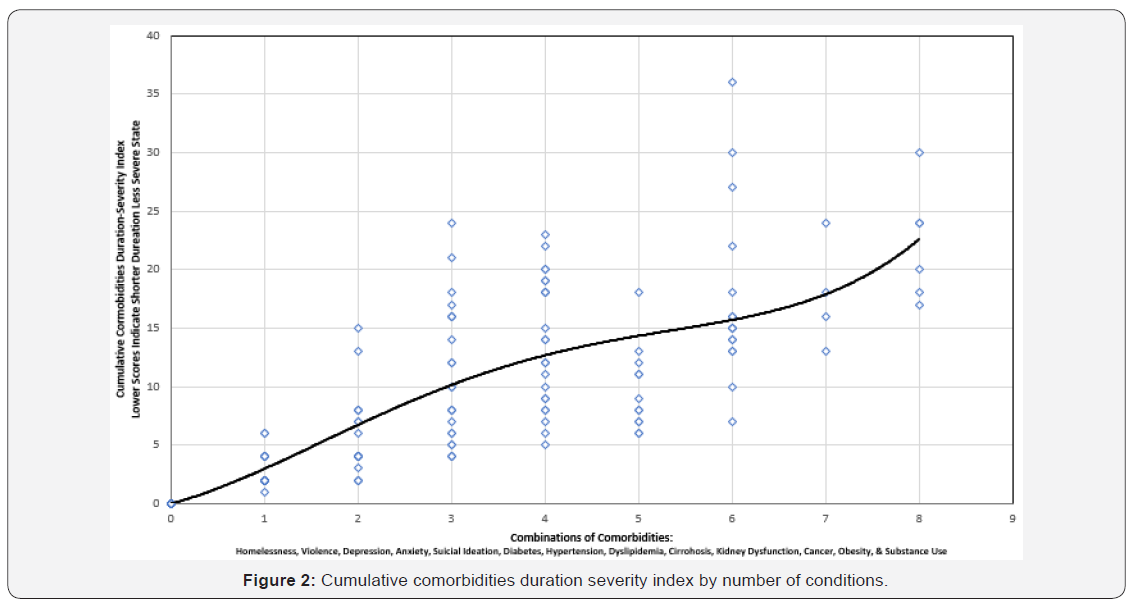

Figure 2 presents the cumulative comorbidities duration severity index. The cumulative index, which ranged from zero to 40, is a summed, multiplicative score, derived by adding the cross products of the duration and severity values for each morbidity. As expected, the index increases, in a non-linear fashion, as the duration and severity of each condition increases. The majority of PLWHs in the sample with one or two comorbidities had an index score less than 10. However, as the number of comorbidities exceeded a count of two, the illness severity score increased by at least 60%, (15/25). At four or more comorbidities, the minimum index score was five, and at seven or more comorbidities, the minimum index score was 12.

Exploratory study 2

Medical case managers screened 96 PLWHAs in the 90 days exploratory testing phase. Thirty-six percent of the clients were female, and 64% were male. Regarding race/ethnicity, 73% of the participants were African American, 22% were Caucasian, and 5% were Hispanic. Ages of the participants ranged from 29-72 years, with a mean age of 46.4 years. Of the clients assessed, 38% had normal nutritional status, 44% were at nutritional risk, and 18% were at high nutritional risk. The most commonly reported nutrition-related factors contributing to nutritional risk were: 1) hypertension (47%), 2) food insecurity (45%), 3) overweight/ obesity (38%), and 4) diabetes (18%).

Discussion

This study has limitations! The two convenience samples are not comparable; therefore, the data they yielded tells us little about the existence of multiple morbidities in the population of persons living with HIV. But the lack generalizability does not mean that all is lost. Study one sought cumulative, prevalence data from health records of in-care PLWHAs who had multiple chronic diseases or states. The public health literature is replete with references to a syndemic-the synergistic interaction of numerous risk factors and health states that exacerbate disease severity [22], but the local HIV information technology management system lacked functionalities to help clinical professionals understand and address the challenges of complex health care needs. To explore options for addressing that health system gap, study one cast a net that assessed the distribution of multiple morbidities. It turn out that psychosocial, (depression, anxiety, and substance use), metabolic, (hypertension, obesity, and diabetes), and sociological, (homelessness and interpersonal violence), risk factors were common, even in a small convenience sample; and after indexing all conditions by taking into account person-years, a positive, non-linear relationship appeared. Years of exposure to diseases and states by number of conditions observed increased in a nonuniform way.

Study two was centered on direct client care practices. In doing so, it paid immediate dividends to Case Managers who could refer or link PLWHs to Dietetic care and it could address the nutrition needs of any PLWH for whom it was indicated. The literature on food insecurity points to immunologic deterioration and elevated risk of morbidities among persons infected with HIV [23]. Minimizing double jeopardy was important. HIV infection compromises the immune system. The lack of access to nutrition food and Food Pantry services inhibit metabolism of ART, which is needed for immune reconstitution. Thus, development of tools and processes to ensure clients receive nutritional assessments is a win-win for service providers and service recipients.

Conclusion

Two successive, exploratory studies were conducted in Duval County. Both studies potentially shared some clients from one HIV CBO. The presence of poor metabolic health in both studies portend risks for future health complications such as heart disease and stroke, among others. On account of ART, PLWHs are living longer and multimorbidity is commonplace. From a health system perspective, strengthening the data coordination and collection infrastructure can facilitate the provision of patient centered care by furthering client-provider discussions on matters of consequence to client’s well-being.

Directions for the future

What should change in the day-to-day implementation of HIV service delivery on the First Coast? The jurisdiction should develop care pathways, which can take the form of care coordination maps. These maps can be an adjunct to disease management screening tools for ensuring that service processes are integrated across all care access points. This prospective innovation takes aim at helping PLWHs experience less fragmented care and fewer unmet needs. The electronic health and social record have implemented multiple patient care screening tools. Emphasis on policy development and contract language should take aim at ensuring robust data collection and analysis to support quality of HIV care, particularly among older adults with HIV, who have multiple morbidities.

Acknowledgment

This project is supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) under grant number H89HA00039, HIV EMERGENCY RELIEF PROJECT GRANTS for grant amount $6,028,703.00 This information or content and conclusions are those of the author and should not be construed as the official position or policy of, nor should any endorsements be inferred by HRSA, HHS or the U.S. Government.

Introduction

Duval County, (a.k.a., Duval), is a region of national significance. It is in the southern region of the United States. The South has 16 states and one territory:

a) Alabama,

b) Arkansas,

c) Delaware,

d) District of Columbia,

e) Florida,

f) Georgia,

g) Kentucky,

h) Louisiana,

i) Maryland,

j) Mississippi,

k) North Carolina,

l) Oklahoma,

m) South Carolina,

n) Tennessee,

o) Texas,

p) Virginia, and

q) West Virginia.

Duval is also home of Jacksonville, an 840 square miles city by land mass—the largest city in the contiguous United States [1]. The Global Positioning System coordinates that define the latitude and longitude of Jacksonville, FL, USA are 30° 19’ 55.8624’’ North and 81° 39’ 20.3292’’ West. It is situated near St. Johns River and is an important tourist attraction for all kinds of travelers [2].”

In addition to tourism, Jacksonville is also known for its military influence. “The waters off Jacksonville… [accommodated] German-U-boat activity during World War II…, and the city was the nation’s busiest military port during the Persian Gulf War, (1990-91) [3].” In 2017, the population of Jacksonville, Florida was 92,064 with a median age of 35.8 years and almost 2/3 , (64%), of residents were in the 18 to 64 years age-group. Four of five, (82%), inhabitants identified as either White, (51%), or Black, (31%). One-tenth of the population is Hispanic. Median household income was $51,497.00 and 15.1% of the populace lived below the poverty line,[4] which “…for a household of four is an annual income of $25,750.00 [5].” For marketing purposes, Florida’s First Coast, or First Coast describes five counties, (Baker, Clay, Duval, Nassau, and St. Johns—BCDNS), that surrounds Jacksonville [6].

Duval County is gaining notoriety. The county’s 2017 health status summary profile illuminates the area’s disease burden. Almost one in five adults, (18.5%), are current smokers compared to 15.5% in Florida. Nearly 1/3 (30.7%), of adults are obese compared to 27.4% in Florida. About 1/5 , (18.9%), of adults could not see a doctor at least once in the past year due to cost compared to 16.6% in Florida. Approaching 1/5 , (16.7%), of adults have been told they had a depressive disorder compared to 14.2% in Florida. Two-thirds, (66.5%), of pregnant women initiated early, (first trimester), prenatal care compared to 78.3% in Florida. Chlamydia cases per 100,000 was 720.8 compared to 470.3 in Florida. Gonorrhea cases per 100,000 was 297.8 compared to 138.5 in Florida [7]. Age-adjusted hospitalization rate per 100,000 for stroke was 317.2 compared to 234.7 in Florida. Ageadjusted hospitalization rate per 100,000 for congestive heart failure was 1,721.8 compared to 1,158.0 in Florida. Age-adjusted hospitalization rate per 100,000 for coronary heart disease was 323.5 compared to 293.7 in Florida [8]. Of 67 Florida counties, in 2019, Duval County ranked 44th on five health outcomes indicators: premature death, poor or fair health, poor physical health days, poor mental health days, and low birthweight [9].

Duval County has a reputation for the Human Immunodeficiency Virus, (HIV). Parallels exist between Duval County, Florida and the southern United States. In 2017, new HIV diagnoses was highest in the South, (52%, 19,968), relative to the West, (19%, 7,270), the Northeast, (16%, 6,011), and the Midwest, (13%, 5,032). Even with standardization of HIV infection rates, the South (16.1/100,000), tops the list, followed by the Northeast, (10.6/100,000), the West, (9.4/100,000), and the Midwest, (7.4/100,000) [10]. In same year, Florida ranked third, (22.9/100,000), on the list of top ten states for new HIV infections among adults and adolescents [11], and Duval County, Florida is one of 48 counties in the nation with high rates of HIV incidence [12]. How is Duval County like the southern United States? Of the five counties, (BCDNS), surrounding Jacksonville, new cases of HIV infections, in 2017, were three to four times higher in Duval County, (32.6 per 100,000), compared to surrounding Counties: Baker, (7.4/100,000), Clay, (9.5/100,000), Nassau, (7.5/100,000), and St. Johns, (10.0/100,000) [13].

Duval County HIV health services professionals give extraordinary attention to the epidemiology of HIV. This attention is matched by the allocation of resources to address the virulence of this pandemic, which, if left untreated, wipes out the host immune system, resulting in poor health and certain death. The advent of and advances in antiretroviral therapy, (ART), treatments support immune system reconstitution and viral suppression, which prolongs life. But research by Deeks & Lewin et al. [14], also showed that the therapeutic benefits of ART comes at a price—occurrences of non-communicable chronic diseases such as cancer, heart disease, kidney disease, liver disease and neurocognitive disease to name a few. A U.S. Veterans Administration study found a 1.5- fold increased risk of myocardial infarction among HIV-infected adults [15]. In contrast, the 36-months, Swiss HIV Cohort Study pointed to excess occurrences of diabetes, osteoporosis, stoke, and myocardial infarction among study participants 50 years and older compared to the younger, (less than 50 years), age-group [16]. HIV medication, which promotes living longer with HIV also requires attention to multimorbidity. “Older persons living with HIV, (PLWH), often defined as age 50 years and older, are a rapidly growing population, with high rates of chronic pain, substance use, and decreased physical functioning.”[17].

Health services professionals in Duval County have also begun to focus on multimorbidity in HIV health services. They recognize that the well documented occurrence of morbidities in aging persons living with HIV, (PLWHs), is a call to action. Because Multiple Chronic Conditions, (MCC), tax human resources in areas such as medical visits, medication adherence, and chronic diseases self-management responsibilities, relative to a single medical condition, there is growing awareness that MCC can decrease quality of life by increasing stressors and disabilities [18].

An inventory of the HIV health system “…free, electronic health and social services information system for Ryan White HIV/AIDS program grant recipients and [subrecipients] [19], highlighted the lack of an index of multiple chronic diseases. A disease index, if populated, can automatically generate a score that prompts clinical action by activating specific clinical pathways. The purpose of this study was to justify development of a cumulative index of common non-communicable diseases among PLWHs that has rapid assessment potential for differentiating clients with complex care needs. The existence of such an electronic instrument can prompt fast and timely alignment of clinical resources for more effective service utilization. The added value of this dimension to current clinical processes can ensure provision of less fragmented HIV care and services.

Materials and Methods

Exploratory study 1

Three HIV Community Based Organizations, (CBOs), completed 121 chart reviews during the first quarter of 2017. Chart selection criteria used convenience sampling and no socio-demographics data were recorded. This study was implemented as an unfunded project using staff already burdened by large, (70+), caseloads, who perceived it largely as data for health policy rather than direct patient care. Project planners yielded to ease of imple mentation as a compromise with health services staff who used personal time to assist with chart extractions. Three Medical Case Managers, (MCMs), used a standardized worksheet to perform the extractions. The worksheet, formatted as an m by n table, had 13 rows and eight columns. The rows represented morbidities of a sociological, psychological, physiological, and chemical brain imbalance origin. Morbidities of a sociological origin focused on homelessness and interpersonal violence. Morbidities of a psychological origin focused on depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation. Morbidities of a physiological origin focused on diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, cirrhosis, kidney dysfunction, cancer, and obesity. The single chemical brain imbalance morbidity examined was substance use disorders. The columns bifurcated into two divisions, one for the duration and the other for severity. The duration column had three levels: less than one year, (coded 1), one to five years, (coded 2), and more than five years, (coded 3). In contrast, the severity column had five levels: normal, (coded 1) mild/minor, (coded 2), moderate, (coded 3), severe/major, (coded 4), and end-stage/extreme, (coded 5). The instructions to MCMs familiar with the convenience sample of clients asked for placing two check marks, (), in each row, if indicated, in the duration and severity columns for every morbidity documented in the charts. Data analysis relied on frequencies, percentages, and the sum of products-which first multiplies then adds the multiplicative values to create a sum. This approach is superior to a simple additive sum [20] of multiple chronic diseases which quantitatively ignores the burden of duration and severity of illness on health and social functioning.

Exploratory study 2

At one of the three HIV CBOs, the University of North Florida, Center for Nutrition and Food Security developed assessments tools. These assessments examined the nutritional status of a convenience sample of clients with HIV and their nutritionrelated complications. Currently, all clients in the local Ryan White network lack access to a validated nutrition-screening tool to identify whether personal health is impaired by the lack of high quality, disease-therapeutic foods in enough quantities. Therefore, the University of North Florida’s nutrition professionals developed a disease-specific nutrition-screening tool based on research and practice experience. Data analysis relied on frequencies and percentages.

Nutrition HIV screening tool & methodology

Appropriate nutrition screening tools is an essential component of comprehensive health care for PLWHs. Hence, the development process included a scoping review of the nutrition literature, identification of nutritional parameters relevant to PLWHs, and discussions about questionnaire length, reading level, format, and frequency and timing of administration. These considerations, among others, have implications for the collection of accurate and valid data. The screening tool has six items that includes insufficient money to purchase food, worry about having an adequate supply of food, body mass index, recent, (past six-months), HIV diagnosis, metabolic and cardiovascular diseases, (diabetes, heart disease or hypertension), contemporary, (past six-months) weight lost, and gastrointestinal issues such as difficulty swallowing, nausea with vomiting, poor appetite, and chronic diarrhea. The additive sum of the points assigned to each item ranged from 0 to 17, which allowed the researcher to triage respondents into three nutritional status categories: normal, (0 to 3), at nutritional risk, (4 to 6), or high nutrition risk, (7 to 17). The rationale for selection of cut-points was facilitation of extensive nutrition screening.

Electronic health & social record updates

Duval County HIV health services Information Technology data manager hard-coded the inventories in the network’s electronic health and social record. Services staff received data collection training and practiced on peers using simulated data. Once trainings were completed, staff evaluated client’s comprehension of inventory questions and statements. Client feedback were incorporated into revisions and trained medical case managers subsequently administered the instrument by screening active clients during a 90-days trial period. The screening protocol also tested a linkage process to connect clients identified at nutritional risk or high nutrition risk to a registered dietitian for a complete nutrition assessment and development of a plan of care. Although exploratory study 2 was unfunded, it garnered strong support from Case Managers because it resulted in direct benefits to clients in referrals and linkages to a Dietitian. Access to timely nutrition services is essential to address underlying unmet needs for food that supports tissue repair and maintenance, immune system support, and metabolism of antiretrovirals [21].

Results

Exploratory study 1

Figure 1 presents the frequency of occurrences of 13 conditions compiled from 121 PLWHAs chart reviews. Comorbidities involving psychological and chemical brain imbalances were most prevalent. This included depression, (20.49%), anxiety, (20.27%), and substance use disorder, (14.70%). The second most prevalent set of comorbidities were metabolic states, identified by hypertension, (10.69%), obesity, (7.13%), and diabetes, (5.79%). On the sociological side, homelessness (6.46%), and interpersonal violence, (5.35%), were most prevalent. None of the remaining conditions exceeded 3% in the sample.

Figure 2 presents the cumulative comorbidities duration severity index. The cumulative index, which ranged from zero to 40, is a summed, multiplicative score, derived by adding the cross products of the duration and severity values for each morbidity. As expected, the index increases, in a non-linear fashion, as the duration and severity of each condition increases. The majority of PLWHs in the sample with one or two comorbidities had an index score less than 10. However, as the number of comorbidities exceeded a count of two, the illness severity score increased by at least 60%, (15/25). At four or more comorbidities, the minimum index score was five, and at seven or more comorbidities, the minimum index score was 12.

Exploratory study 2

Medical case managers screened 96 PLWHAs in the 90 days exploratory testing phase. Thirty-six percent of the clients were female, and 64% were male. Regarding race/ethnicity, 73% of the participants were African American, 22% were Caucasian, and 5% were Hispanic. Ages of the participants ranged from 29-72 years, with a mean age of 46.4 years. Of the clients assessed, 38% had normal nutritional status, 44% were at nutritional risk, and 18% were at high nutritional risk. The most commonly reported nutrition-related factors contributing to nutritional risk were: 1) hypertension (47%), 2) food insecurity (45%), 3) overweight/ obesity (38%), and 4) diabetes (18%).

Discussion

This study has limitations! The two convenience samples are not comparable; therefore, the data they yielded tells us little about the existence of multiple morbidities in the population of persons living with HIV. But the lack generalizability does not mean that all is lost. Study one sought cumulative, prevalence data from health records of in-care PLWHAs who had multiple chronic diseases or states. The public health literature is replete with references to a syndemic-the synergistic interaction of numerous risk factors and health states that exacerbate disease severity [22], but the local HIV information technology management system lacked functionalities to help clinical professionals understand and address the challenges of complex health care needs. To explore options for addressing that health system gap, study one cast a net that assessed the distribution of multiple morbidities. It turn out that psychosocial, (depression, anxiety, and substance use), metabolic, (hypertension, obesity, and diabetes), and sociological, (homelessness and interpersonal violence), risk factors were common, even in a small convenience sample; and after indexing all conditions by taking into account person-years, a positive, non-linear relationship appeared. Years of exposure to diseases and states by number of conditions observed increased in a nonuniform way.

Study two was centered on direct client care practices. In doing so, it paid immediate dividends to Case Managers who could refer or link PLWHs to Dietetic care and it could address the nutrition needs of any PLWH for whom it was indicated. The literature on food insecurity points to immunologic deterioration and elevated risk of morbidities among persons infected with HIV [23]. Minimizing double jeopardy was important. HIV infection compromises the immune system. The lack of access to nutrition food and Food Pantry services inhibit metabolism of ART, which is needed for immune reconstitution. Thus, development of tools and processes to ensure clients receive nutritional assessments is a win-win for service providers and service recipients.

Conclusion

Two successive, exploratory studies were conducted in Duval County. Both studies potentially shared some clients from one HIV CBO. The presence of poor metabolic health in both studies portend risks for future health complications such as heart disease and stroke, among others. On account of ART, PLWHs are living longer and multimorbidity is commonplace. From a health system perspective, strengthening the data coordination and collection infrastructure can facilitate the provision of patient centered care by furthering client-provider discussions on matters of consequence to client’s well-being.

Directions for the future

What should change in the day-to-day implementation of HIV service delivery on the First Coast? The jurisdiction should develop care pathways, which can take the form of care coordination maps. These maps can be an adjunct to disease management screening tools for ensuring that service processes are integrated across all care access points. This prospective innovation takes aim at helping PLWHs experience less fragmented care and fewer unmet needs. The electronic health and social record have implemented multiple patient care screening tools. Emphasis on policy development and contract language should take aim at ensuring robust data collection and analysis to support quality of HIV care, particularly among older adults with HIV, who have multiple morbidities.

Acknowledgment

This project is supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) under grant number H89HA00039, HIV EMERGENCY RELIEF PROJECT GRANTS for grant amount $6,028,703.00 This information or content and conclusions are those of the author and should not be construed as the official position or policy of, nor should any endorsements be inferred by HRSA, HHS or the U.S. Government

Comments

Post a Comment