Abandonment of Female Genital Mutilation within a generation: what worked and what next?_Juniper publishers

Global Journal of Reproductive

Medicine Juniper

Publishers

Abandonment of Female Genital Mutilation

Authored by: Oto Buraimo*

Introduction

Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting (FGM/C) also known as ‘female circumcision’ or ‘female cutting’ involves the non-therapeutic partial or complete removal of external female genitalia for non-medical reasons but largely due to cultural, religious and social reasons [1]. The World Health Organisation (WHO) has broadly classified FGM/C into four types: clitoridectomy, excision, infibulations and other [2]. The act remains a gross human rights violation specifically against girls and women in their early adolescence. Besides the obvious physical agony experienced by women subjected to FGM/C and death in certain cases, the act leaves detrimental lifelong psychological and emotional scars including chronic infection, recurrent pains during sexual intercourse, urination and menstruation and obstetric complications during childbirth [3]. A systematic review of comparative studies between women with FGM/C and without FGM/C concluded that those with FGM/C are more likely experience pain during sexual intercourse and reduced sexual desire and satisfaction, which completely deprives the victims of FGM/C optimum control over their sexuality [4].

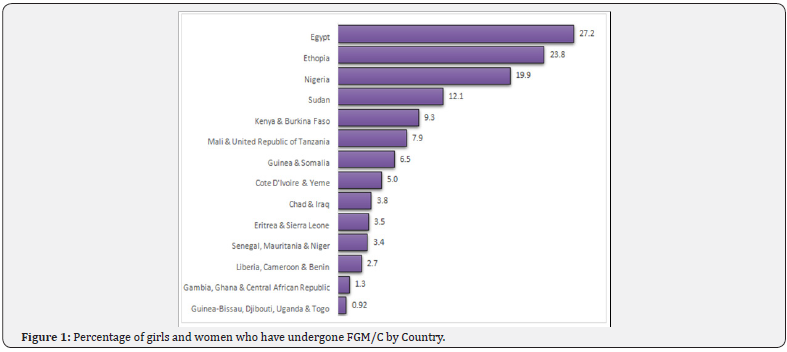

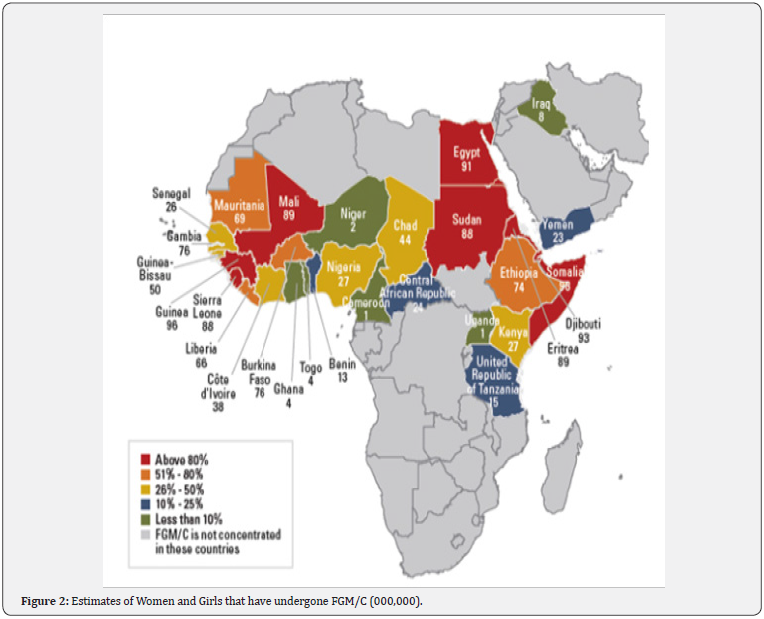

Although the practice of FGM/C is endemic in about 29 countries in Africa, Asia and Middle East, victims are scattered across the globe largely due to globalisation and international migration. The findings from a UNICEF led national survey in over 35 countries show that over 200 million women have undergone FGM/C, a practice which is disproportionately rife in countries like Somalia, Guinea, Djibouti and Egypt where over 90 percent of girls and women aged 15 to 49 years have undergone FGM/C at some point in their lifetime [5] (Figure 1). In absolute numbers, Egypt, Ethiopia, Nigeria, Sudan, Kenya and Burkina Faso account for almost 100 million (approximately 50 percent) of the entire global cases of FGD (Figure 2). Moreover, 3 million girls and women stand the risk of undergoing FGM/C annually and more recent statistics show that 15 million girls would have undergone FGM/C by 2020 in the absence of apt intervention, which will invariably aggravate the already troubling statistics of girls and women that are managing the lifelong consequences of FGM/C [6,7].

Oftentimes, perpetuators perceive this dangerously life altering act as a way to curb promiscuity and invariably promote fidelity among FGM/C victims [3]. Other underlying reasons for the practice of FGM/C relates to the promotion of the marriage ability of girls and preservation of their virginity in order to prevent shame following marriage and as well enhance social acceptance within communities where the practice of FGM/C is rife [8,9]. The practice of FGM/C has ethnicity and religious dimension likewise as observed in the countries like Benin, Togo and Niger. In Benin, girls and women with Peulh ethnicity are seven times more likely to undergo FGM/C compared to counterparts from Adja and Fon ethnicity. Moreover, Muslim girls and women are more likely to undergo FGM/C compared to Christian counterparts in Togo whereas Christian girls and women are more likely the experience the same in Niger.

Why female genital mutilation/cutting continues

Despite the lifelong adverse effect of FGM/C on the physical and mental health, girls and women that have undergone FGM in countries like Gambia perceive the practice as being beneficial and hence want FGM/C to continue. Also, FGM/C survivors with lower levels of literacy in Sudan and Ethiopia support the continuation of FGM/C, which demonstrates how ingrained the practice remains within some communities [5]. An understanding of the drivers of FGM/C is an invaluable first step at ending the crisis. In two systematic reviews of 51 studies involving home-based and foreign-based indigenes of communities where FGM/C is highly prevalent, cultural tradition, religious beliefs, and sexual morals were the reasons for the continuance of the practice [10,11]. The cultural, social, ethnic and sometimes religious underpinnings of FGM/C bring the complexities of eradicating the practice to the foreground. This potentially explains the persistent practice of FGM/C despite concerted eradication efforts by global advocates, policy makers and national governments. Nonetheless, these efforts have yielded marginal returns as the prevalence of FGM/C has declined steadily over the last three decades despite the burgeoning global population growth within the same period [6].

Interventions that have worked

Interventions toward abandonment of FGM/C have adopted many approaches. Some of the widely evaluated methods are community-led approaches, public declarations, conversion of excisers, alternative rituals, training of health workers as change agents, health hazards approaches, and legal sanctions [12,13].

Community-led approaches: They focus on empowering girls, women and community members to self-examine their cultural practice of FGM/C and abandon it for their own benefit [14]. Success of this approach is usually context-dependent. For example, a similar programme run in paired communities Senegal, Burkina Faso and Somalia resulted in markedly different rates of FGM/C abandonment across the three countries [10,15,16].

Public declarations: These are open statements by a large group in a community to abandon FGM/C. These declarations can signify a readiness to change or an actual abandonment of FGM/C. However, public declarations are rewards of effective intervention, programmes that solicit statements from authoritative subgroups such as eminent religious leaders or excisers rarely results in behavioural change if the community buy-in is low [12].

Conversion of excisers: Some interventions target excisers, majority of whom are traditional practitioners, with the aim of training them on female anatomy and the hazards of FGM/C and convincing these practitioners to stop performing FGM/C. Subsequently, ex-excisers are rewarded with training and funding for alternative source of livelihood. Although this approach offers an easy measure of the success of intervention, an ex-practitioner may return to the trade covertly or by proxy and other aspiring exciser may fill the vacant positions [17].

Alternative rituals: Many communities perform FGM/C as a part of rite of passage from childhood to womanhood for their adolescent girls. Alternative rites interventions proffer a replacement of FGM/C-included rite of passage with alternative rite while still upholding the tradition of the community. For example, in Kenya and Sierra Leone, excising rituals were replaced non-cutting versions during the ritual seasons [18]. However, the use of alternative rites are limited to context where FGM/C is part of rite of passage and not elsewhere.

Health hazards approaches: The health risks of FGM/C are communicated via health information materials and media. It is the oldest and most popular method whereby individuals and community groups are informed on the health hazards of FGM/C by lay workers, health personnel, community facilitator or civil society staff [19]. The increased knowledge are expected to stimulate critical thinking that will eventually foster an abandonment of FGM/C [20]. Poorly formulated, judgmental and ‘westernised’ health information have been linked with disbelief, resistance, defence reaction, outright disregard and medicalization of FGM/C [21].

Training of health workers as change agents: Health professionals are influential members of the community that can foster healthy changes. Thus, intervention have focused on health workers with the aim of educating them on FGM/C, preventing them from practicising it, training them on identifying and treating associated complications, and ultimately deploying them as change agents [22]. However, some health workers might be resistant to abandoning FGM/C owing to their socio-cultural beliefs. In fact, the literature is rife with medical proponents of FGM/C [23,24].

Legal sanctions: Legislative measures against FGM/C have been adopted in many communities to prevent FGM/C. Numerous African and Western countries have formally enacted laws that ban FGM/C and impose prosecutions, punishment and/ or fines [25,26]. Laws may make FGM/C go underground and may also deter sufferers of immediate complications of FGM/C from seeking prompt medical treatments [27].

What we can do differently

Throughout the four decades that interventions against FGM/C have been ongoing, many successes have been achieved, yet a lot more ground awaits covering. Findings from research have shown that ‘a one size fit all’ approach will not accelerate the progress towards elimination of FGM/C. Contrariwise, interventions that have worked have been those that mobilised multi-sectors, assembled many actors, ran from and with the community, and ensured sustained actions [2]. Therefore, programmes should be comprehensive and holistic; methods should anchor on a background of community participation and involvement; sensitive, tailored, locally relevant health information should be used as a tool to foster change; positive reinforcement should be supplied from a network of religious and community leaders, health professionals and peer group incorporate; and an FGM/C supportive legal framework should be enacted and enforced at all level of governance.

Conclusion

Many individuals, agencies and organisations have conducted research and are planning more studies. For example, since 1996, the Population Council with its partner partners like DFID, USAID, UN Agencies, Wallace Global Fund, Comic Relief and Norad have focused on research in 13 countries where FGM/C is highly prevalent [28]. However, scores of research gaps are still evident, studies designs need to improve, and research should comply with internationally agreed indicators [29]. Finally funding fuels progress and many funding agencies have helped with the progress on eliminating FGM/C so far, but funding gaps still need to be filled and very quickly too [2].

Comments

Post a Comment