Clinical Dilemmas and Risks of Misdiagnosis and Mismanagement Associated with Endogenous Caesarean Scar Pregnancy: A Case Series and Literature Review

Global Journal of Reproductive Medicine Juniper Publishers

Abstract

A caesarean scar pregnancy (CSP) is a pregnancy that

implants into the myometrium at the site of a previous uterine incision.

In this paper, we present three cases of women affected by caesarean

scar implantations. Each case presented differently and was managed in

separate ways. We describe their differing presentations and care as

well as reflecting on how such women may be better cared for. Endogenic

CSPs grow into the uterine cavity and can easily be mistaken for a

normal pregnancy implantation. Differentiation can often only be seen at

early gestations. All women with a previous uterine scar should

potentially be offered early trans-vaginal ultrasound to correctly

diagnose the implantation site. However, in many women, the diagnosis is

not suspected until a complication arises. We advocate for there to be a

higher index of suspicion for CSPs during early pregnancy ultrasound

and that all practitioners performing such scans should be trained to

allow a confident diagnosis of CSP.

Keywords: Caesarean scar pregnancy; Caesarean sections; Intravenous; Ultrasound scan; Human chorionic gonadotrophin

Abbreviations:

CSP: Caesarean Scar Pregnancy; TVS: Trans Vaginal Ultrasound; CS:

Caesarean Sections; TOP: Termination of Pregnancy; MVA: Manual Vacuum

Aspiration; IV: Intravenous; A&E: Accident &Emergency; TAS:

Trans Abdominal Scan; UV: Ultrasound Scan; HCG: Human Chorionic

Gonadotrophin

Introduction

Caesarean scar pregnancy is defined as implantation

into the myometrium defect occurring at the site of the previous uterine

incision. The prevalence of CSP is estimated to be approximately 1 in

2000 pregnancies and these pregnancies may be ongoing potentially viable

pregnancies or miscarriages within the scar. 37 The diagnostic criteria

described for diagnosing caesarean scar implantation on transvaginal

ultrasound include:

I. Empty uterine cavity.

II. Gestational sac or solid mass of trophoblast

located interiorly at the level of the internal as embeded at the site

of the previous lower uterine segment caesarean section scar.

III. Thin or absent layer of myometrium between the gestational sac and the bladder

IV. Evidence of prominent trophoblastic/placental circulation on Doppler examination.

V. Empty endocervical canal.

Thirteen percent of reported ca SES of CSP were

misdiagnosed as intrauterine or cervical pregnancies at presentation.

The true prevalence of caesarean scar pregnancies is likely to be

somewhat higher than estimated in the literature as some cases will end

in the first trimester, either by miscarriage or termination, and go

unreported and undiagnosed. There is a spectrum of severity CSP is

defined as implantation into the myometrial defect occurring at the site

of the previous uterine incision. The prevalence of CSP is estimated to

be approximately 1 in 2000 pregnancies and these pregnancies may be

ongoing potentially viable pregnancies or miscarriages within the scar.

The diagnostic criteria described for diagnosing caesarean scar

implantation on transvaginal ultrasound include:

i. Empty uterine cavity.

ii. Gestational sac or solid mass of trophoblast

located anteriorly at the level of the internal os embedded at the site

of the previous lower uterine segment caesarean section scar.

iii. Thin or abse nt layer of myometrium between the gestational sac and the bladder.

iv. Evidence of prominent trophoblastic/placental circulation on Doppler examination.

v. Empty endocervical canal.

Thirteen percent of reported cases of CSP were

misdiagnosed as intrauterine or cervical pregnancies at presentation.

The true prevalence of caesarean scar pregnancies is likely to be

somewhat higher than estimated in the literature as some cases will end

in the first trimester, either by miscarriage or termination, and go

unreported and undiagnosed. There is a spectrum of severity. A caesarean

scar pregnancy (CSP) is a pregnancy that implants into the myometrium

at the site of a previous uterine incision. They are one of the rarest

forms of ectopic pregnancy with an incidence of 1:1800 pregnancies [1].

Such pregnancies may result either in an early miscarriage or a viable

ongoing pregnancy within the scar. Since the first report by Larsen and

Solomon in 1978 [2], the incidence of these pregnancies has been increasing, reflecting rising caesarean section rates.

The natural history of such pregnancies has not been

fully elucidated. The morbidity and early indicators of outcomes are yet

to be fully described. It is suggested placenta acreta is the end point

of an ongoing caesarean scar ectopic pregnancy [3]. Management options are variable and the best way to prevent recurrence unclear [4].

As with other non-tubal pregnancies misdiagnosis is common resulting in

mismanagement and poorer outcomes. In addition to a comprehensive

history, transvaginal ultrasound (TVS) is the primary modality for

diagnosis. A recent RCOG guideline has emphasized ultrasound diagnostic

criteria, however, these have not been validated [4].

In this paper, we present three cases of women affected by caesarean

scar implantations, describing their presentation and management as well

as reflecting on how such women may be better cared for.

Case Study 1

A 30-year-old Afro-Caribbean, gave a history of two

previous caesarean sections (CS) and a first trimester termination of

pregnancy (TOP). The surgeon performing her last CS had advised her

against future pregnancies due to a very thin lower segment. As a

result, when she inadvertently fell pregnant she opted to terminate the

pregnancy. TVS at the local TOP service suggested that the pregnancy was

'outside the womb' and referral was made to a neighbouring early

pregnancy unit where she was scanned by a sonographer. TVS here showed a

viable seven-week intrauterine pregnancy with an irregularly shaped

gestational sac. Consequently, she returned to the termination service

for her surgical procedure at 9 weeks and 3 days. She underwent a manual

vacuum aspiration (MVA) under sedation. This was complicated by heavy

vaginal bleeding and the operator was concerned about a possible uterine

perforation. The patient was given uterotonics (syntocinon 5+51U IV,

misoprostol 1mg PR) as well as intravenous (IV) tranexamic acid (1g). A

vaginal pack was inserted and ambulance transfer to our accident and

emergency (A&E) resuscitation room was arranged.

On arrival, her blood pressure was 96/58mmHG with a

heart rate of 89bpm, her haemoglobin estimation was 70g/dL. A

transabdominal ultrasound scan (TAS) showed a bulky uterus with a clot

in the cavity and a second mass, presumed clot, above the fundus. She

was consented and transferred to theatre. She underwent laparoscopy with

Palmers point entry. There were dense adhesions from her previous CS

scar resulting in the uterus being attached to the anterior abdominal

wall. These adhesions were divided and the bladder reflected, revealing a

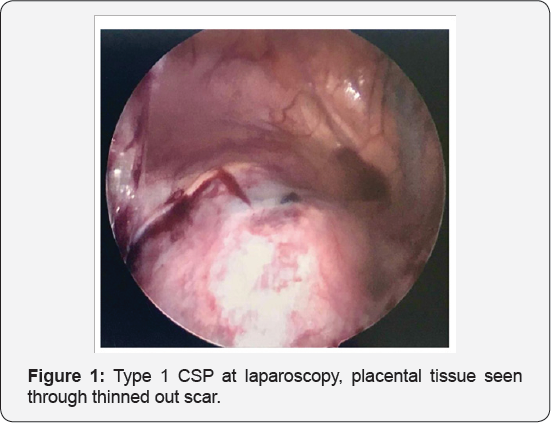

thinned out lower segment scar and a ballooning above the cervix (Figure 1).

A diagnosis of a CSP was made. Using a harmonic scalpela the lower

segment of the uterus was opened and the placental bed site excised. A

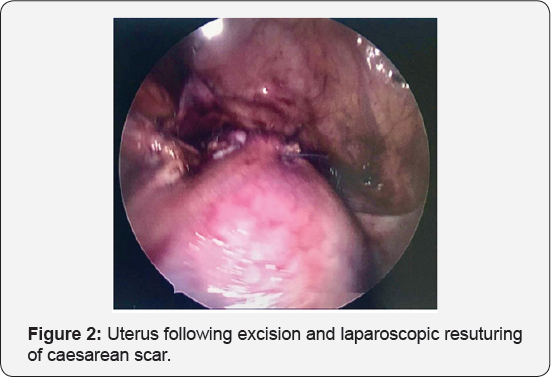

400ml blood clot was removed from inside the uterus and the defect was

closed in 2 layers, with intracorporeal no 1 polysorb suturesa (Figure 2).

She was transfused three units of red blood cells and discharged home

on day five. Human chorionic gonadotrophin (HCG) levels had normalized

by day 40 and she was advised to avoid pregnancy for at least six

months. Histopathological examination of the excised portion confirmed

placental implantation site tissue.

Case Study 2

A 41-year-old woman South Asian lady presented with a

history of two full term deliveries, the first by CS for breech

presentation and the second by spontaneous vaginal delivery. She had had

five miscarriages and one surgical TOP. One of the miscarriages was of a

molar pregnancy. Her initial presentation to our EPAU was with groin

pain. A TVS showed a viable intrauterine pregnancy of 7 weeks and 6 days

gestation and an HCG level of 61,016. The pregnancy sac was noted to be

low just above the cervix. Three weeks later she attended an off-site

clinic requesting surgical TOP for social reasons. She underwent MVA

under sedation. She bled 300ml during the procedure and then collapsed

in recovery with a further bleed of 500ml. She was given uterotonics

(syntocinon 5IU IV and syntometrine 5IU IM) and IV tranexamic acid (1g).

A vaginal pack was inserted and she was transferred via ambulance to

our units A&E resuscitation room. Upon arrival, she had a heart rate

of 91 and blood pressure of 126/59, bedside haemoglobin estimation was

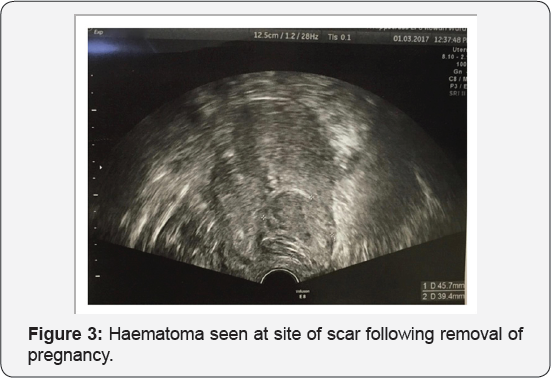

67g/dl. TAS at the bedside showed a haematoma at the site of the

previous caesarean scar but no intra-abdominal free fluid. The vaginal

pack was removed and she was given 1mg of rectal misoprostol and a 40IU

infusion of syntocinon. Bleeding settled and she was transferred to our

ward for observation and transfusion of three units of red blood cells.

HCG was 4225mIU/ml. TVS the following day showed a 45x45x39mm caesarean

scar haematoma (Figure 3), repeat scan 6 weeks later showed complete resolution of this lesion.

Case Study 3

A 38-year-old Caucasian lady, presented with

abdominal pain, vaginal bleeding and a positive urinary pregnancy test.

She gave a history of one previous CS for foetal distress five years

previously. TVS showed a gestational sac implanted low in the uterine

cavity with early foetal demise. Subsequent TVS performed by a

consultant, immediately prior to a scheduled MVA procedure, showed a

very vascular and irregular gestational sac measuring 42x32x45mm lying

low in the uterus near the CS scar with only a thin layer of covering

myometrium. A CSP was suspected and a decision was made to perform an

evacuation of retained products of conception under general anaesthetic

in anticipation of potential complications. A suction evacuation was

performed with ultrasound guidance. The theatre team were prepared for

large blood loss and appropriate blood products had been made available.

Following removal of the pregnancy there was brisk bleeding. TAS

confirmed an empty cavity and there was no suspicion of perforation. She

received misoprostol (1mg PR), syntocinon 5+5iu IV and 40IU infusion,

carboprost IM 250mg twice and IV tranexamic acid (1g) alongside bimanual

compression for 10-15 minutes compression. Her bleeding settled with a

measured blood loss of 2250ml. Starting haemoglobin was 138g/dl, she

received two units of red blood cells and haemoglobin following these

was 113g/dl. She remained on the ward overnight for observation and was

given three, four hourly doses of oral misoprostol. There was no further

blood loss she was discharged the following day.

Discussion

CSPs are a relatively modern phenomenon. The

increasing incidence is thought to be either due to increased reporting

or increasing global caesarean section rates. The symptoms of CSP do not

differ from those of other non-tubal pregnancies but they occur

exclusively in women who have had previous CS, occurring in about 6.1%

of women with an ectopic pregnancy and at least one CS [5].

The pathophysiology of caesarean scar pregnancies remains unclear. It

is likely that a CSP forms following invasion of the implanting

blastocyst through a microscopic niche in the healed uterine scar.

Additionally, there may be a more global impact on the endometrium due

to the very presence of scar tissue which allows aberrant implantation [6].

CSPs form a clinical spectrum from a partial implantation over a thick

scar, which grows into the uterine cavity, to a pregnancy fully located

outside the uterine cavity, only connected to the uterine cavity via a

thin tract. Two main types have been described [7].

The first type, also known as type 1 or endogenic,

implants over the scar but proceeds to develop within the uterine

cavity. It may appear as a viable intrauterine pregnancy, complete with

yolk sac, embryo and cardiac activity, and progress to a viable

gestational age with possible problems with placentation [8].

Type 2 or exogenic scar ectopics are pregnancies that implant more

deeply within the scar and grow in the direction of the serosal surface

of the uterus towards the broad ligament or bladder. A thin layer of

myometrium may be seen at early gestations between the gestational sac

and the serosa. In two thirds of cases this will measure less than 5mm [9].

As the pregnancy grows this layer thins and disappears. Consequently,

the pregnancy bulges through the scar defect with a much greater rate of

early uterine rupture and subsequent haemorrhage

Ultrasound remains the most used modality for diagnosis. A recent guideline from the RCOG [4] describes criteria for diagnosis which include:

a. Empty uterine cavity.

b. Gestational sac or solid mass of trophoblast

located anteriorly at the level of the internal os embedded at the site

of the previous lower uterine segment caesarean section scar.

c. Thin or absent layer of myometrium between the gestational sac and the bladder.

d. Evidence of prominent trophoblastic/placental circulation on Doppler examination.

a. Empty endocervical canal: Ultrasound can also be

used to differentiate between type 1 and type 2 CSP. In endogenic (type

1) CSP, the deformity seen on ultrasound is less apparent as the

implantation grows towards the uterus. The ultrasound image consequently

can appear as a viable intrauterine pregnancy [10].

In these types of low implantation endogenic CSP, differentiation from a

normal pregnancy can often only be made by ultrasound at earlier

gestations [3]. For optimal management of CSP a high index of suspicion and early diagnosis is the key to successful outcomes [11]. This also allows women to make informed choices based on potential morbidity [4].

As a rule of thumb, taking the woman's wishes into consideration, CSP

diagnosed at early gestation should be terminated. The decision is

easier for non-viable or unwanted pregnancies as opposed to wanted

pregnancies where a heartbeat is identified on scan. Though there have

been reports of successful deliveries an expectant approach increases

the risk of a morbidly adherent placenta with likely caesarean

hysterectomy and significant haemorrhage [12-15].

An additional question raised by 2 of our 3 cases is

whether it is safe for women who want to have a TOP and have a history

of CS to have this performed in community based TOP centres or whether

they should be performed in centres with options for laparoscopic

surgery or intensive care facilities should the need arise.

There are very few randomised studies of the management of CSP. Most evidence comes from case series and reviews [4], there is one systematic review of outcomes [16]. Current evidence regarding differing management options has recently been reviewed [6].

Conclusion

Literature suggests that we are not over diagnosing

caesarean scar pregnancies. Most case reports, including our own,

describe situations where the diagnosis was only suspected following

significant maternal bleeding after instrumentation of the uterus for

management of a miscarriage or termination. The key to the diagnosis is a

high index of suspicion and a TVS performed by an appropriately

experienced and skilled operator. Up to 13.6% of CSPs are misdiagnosed

as an inevitable miscarriage or a cervical ectopic [6].

Interventions in such cases without the necessary preparations for

major haemorrhage can lead to increased morbidity and hysterectomy.

Strong Doppler colour flow and the presence of the 'sliding sign'

differentiates a scar ectopic from a low lying inevitable miscarriage.

Ballooning of and a sac within the cervix are the hallmarks of a

cervical ectopic pregnancy.

We recommend that all women with a history of

caesarean section are referred for an early viability TVS with an

appropriately skilled sonographer or gynaecologist to rule out a

diagnosis of caesarean scar ectopic. This should be performed before

routine dating scans, to allow time for counselling and management

should a CSP be diagnosed. To facilitate this; sonographers, nurse

specialists and doctors performing these scans in early pregnancy units

should be encouraged to consider the diagnosis and be appropriately

trained in the ultrasound diagnosis of CSP. We recommend that all women

undergoing TOP with a caesarean section scar site implantation or

suspected Caesarean ectopic pregnancy have their procedure performed in

units with facilities not only to cope with major haemorrhage but also

to perform laparoscopic surgery should this be needed.

Additional Files

To Know More About Please Click on: Global Journal of Reproductive Medicine https://juniperpublishers.com/gjorm/index.php

To Know More About Open Access Journals Publishers Please Click on: Juniper Publishers

Comments

Post a Comment